|

|

| gardri @ mail.ru |

| GARDRI — 25 years in Russia |

|

|

| Teachers |

|

|

|

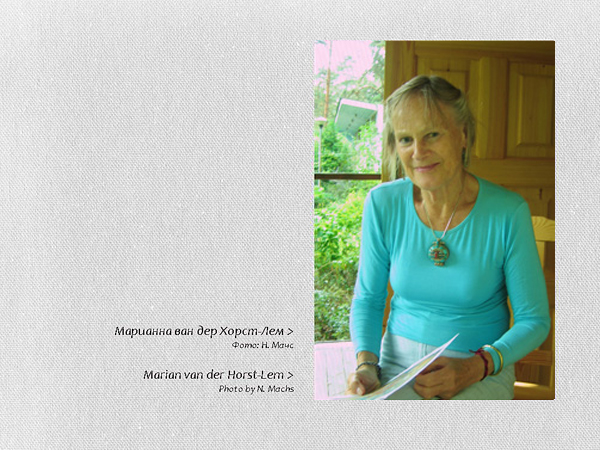

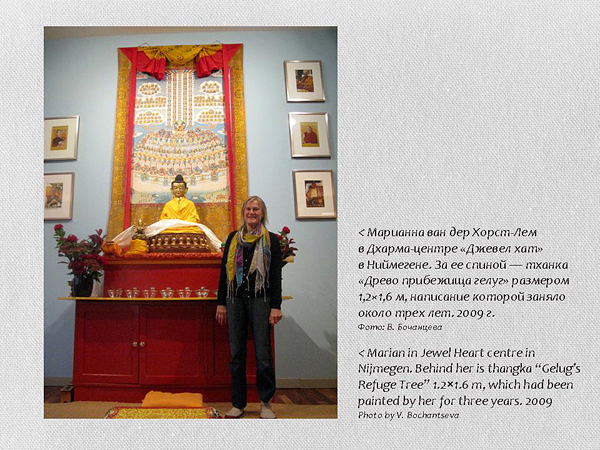

Marian van der Horst-Lem |

|

Marian van der Horst-Lem lives in

Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Before her meeting with Tibetan culture, she

specialized in the fabric painting. Marian was strong impressed by Buddhist

murals in Indian caves. |

|

|

|

|

|

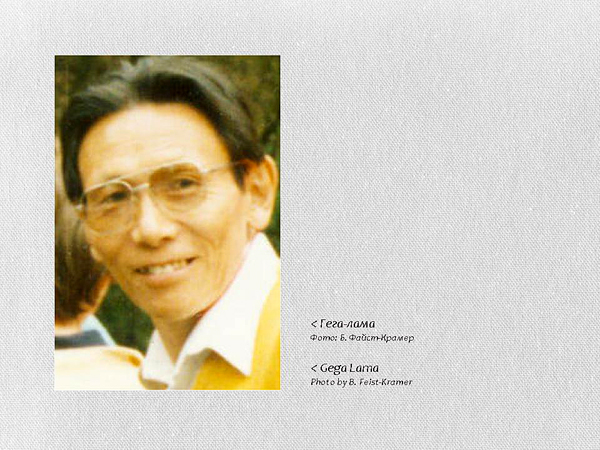

Gega Lama (dge dga' bla ma) |

|

Gega Lama (1931-1996) was not only outstanding master of thangka-painting but also a sculpture, founder of ritual things, dancer and singer. He was born in the village of Rinchen

Ling, Eastern Tibet. At his eight he began studying Tibetan calligraphy with

Lama Drontsay and at eleven entered the monastery Chokor Namgyal Ling at

Tsabtsa where he studied Buddhist doctrine, dance, painting and music. Gega

Lama's first painting teacher was Lama Chokyong. In 1947, at his sixteen, Gega Lama became a student of the greatly respected painting teacher,

Thangla Tsewang (1902–1989). Gega Lama remembared about his Teacher,

“From a young age, he was very talented, filled with a deep desire to create

representations of the Buddha's body, speech, and mind. He became

famous and had many students. Without showing partiality, he developed their

various talents with many different methods of teaching. Being a

good-humoured man, he made many jokes, and there was always the sound of

laughter among his students. He had a vast knowledge of the Dharma, so

he could unerringly specify the characteristics of the different deities,

peaceful or wrathful forms, the categories of the higher or lower tantras,

the Sarma or Nyingma viewpoints, and so forth. He was also recognised

as an emanation artist, thus being an artist of exceptional ability.

Together with his students, he worked unceasingly on his paintings from his

youth till the age of eighty-five.” Further years Gega Lama lived in Katmandu,

Nepal; there he worked in his studio and tough students — he put much effort

in their education. He was the director of the Department of Fine Arts

in the University of Rumtek in India. Gega Lama painted many thangkas for

Beru Khyentse Rinpoche, Kalu Rinpoche, Dhingo Khyentse Rinpoche, etc.; in 1991, he built big Namgyal Stupa in Manduvala village, Indian Lingtsang,

in memory of lama Ogyan (1933-1990); also he created a lot of

handcrafts such as vajras and bells, statuettes and other ritual things. See Gega Lama's book Principles of Tibetan Art” (in two volumes, 1983, Dharamsala's edition) on BDRC. |

|

|

|

|

|

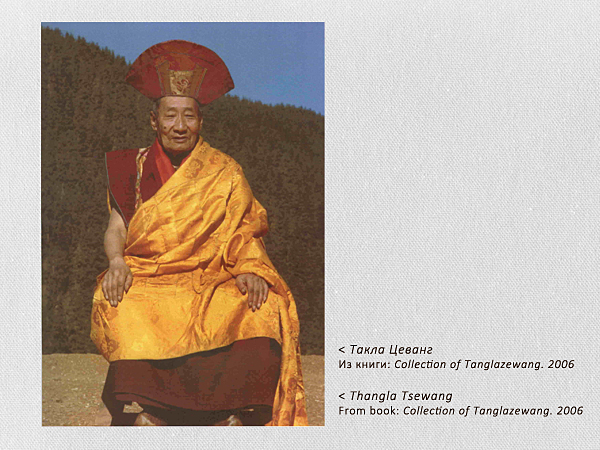

Thangla Tsewang (thang lha tshe dbang) 唐拉泽旺 |

|

Thangla Tsewang (1902-1989) was born in 1902 in the region of Arap in Derge Palyul in Eastern Tibet. Gifted from an early age, he studied painting and sculpture under two accomplished Gardri masters, Wari Lama Lodro, who excelled at drawing, and Payma Rabten, a holder of the Karsho lineage, who excelled in coloring. Beginning with this extensive training in the arts, Thangla Tsewang spent his entire life in ceaseless creative activity. The previous H.E. Tai Situ Rinpoche, Payma Wangchok Gyalpo, once said that his paintings were so good as to be fit to be installed in shrines without being formally consecrated. It is said that whoever viewed his work, whether they were discerning or not, found the forms illuminating and in accord with the import of the sutras and tantras; his work was considered authentic by all.

From book: D. Jackson. A History of

Tibetan Painting. 1996. p. 327-328

new! Biography

of Thangla Tsewang Translated by Реmа

Wangyal, edited by Michael Sheehy |

|

|

|

Video-interview with Marian van der Horst-Lem (Moscow, Russia, 2011) See YouTube Interview was taken in Buddhist Gar under Moscow (Pavlov Posad) during the traditional Summer retreat of thangka painting. |

|

|

|

Interview Together with Marian in interview took part her students: Alla Fadeeva, Zalina Toguzaeva, Vadim Gudkov and Kristina Popova. Moscow, 2009. |

|

|

| Question: In the beginning we would like to know, of course, how you started to paint thangkas, who were your first teachers. We know it, of course, but… |

|

Answer: I was an artist; I was educated as an artist.

But I was never really satisfied, there was always lacking something.

Happily, I found, by my traveling to India, thangka and Buddha, than I got a

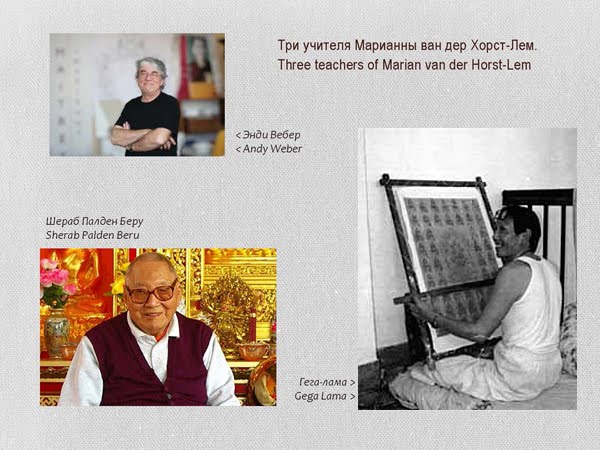

possibility to study by Andy Weber, so he was my first teacher. I studied

some weeks during some summers with him and then he said: "You go to a

Tibetan master, you have to go. I don't teach you anymore" and he did not

give his reason. So we found each other, I found Gega Lama. He came very

late, because he intended to be at the beginning of July in Belgium, and by

the end of August he was not still there. Only a few days were left, so I

had two or three days together with him. He gave me some things to do so

that I could draw at home to practice. I bought the big book, "Principles of

Tibetan Art" by his hand. It was available at that time.

Then, also I went to Scotland to Sherab Palden Beru two or three times, something like that. It was a Buddhist center, Kagyu center. There I painted on a big thangka, one of a series of several thangkas for the big gompa, each of them 3 meters wide and about 2 meters high. In Scotland I painted a big thangka. And he knew I was a painter already. I had to prove myself as a painter so I painted a ball; I shaded it, something like an orange. I made it very natural. And he said, OK, you can paint. It was funny because Sherab Palden Beru could not talk English, he could only say "Good night", or "Good morning", so he could not teach us with words but he taught us in a different way, and it was amazing what we learned. I went several times to Scotland for many weeks and visited then also Andy Weber who lived in the lake-district very close to Scotland. |

| Question: And how did you get to know about him? |

| Answer: Andy Weber told me that there was a big need of thangka painters in Scotland. You can go there, you don't have to pay there; you can stay there and help them. So I went there several times. And I went every year to Gega Lama, during eight years. And I was amazed: he had so many students, twenty at once — at one course, at one summer. Very, very few happened to be a painter: I see only two people, three people at most, who became professional painters. Then I thought: you must have the karma, all the situations have to give you the possibilities, enable you. So this is not a very big story. |

| Question: So, your teachers were Andy Weber, Sherab Palden Beru… |

| Answer: …and Gega Lama. Gega Lama was my main teacher. But Andy Weber put me on the path; he gave me the initial instructions during the first years. He taught me also how to prepare the gold, it was very important. He was really a very good first teacher, he is a very good person, and I still like him and visit him when he is in Holland. |

| Question: Tell about your first coming to Russia. |

| Answer: Funny, in fact I was not invited, but Bruni Feist was invited, she is also a thangka painter, one of the three students of Gega Lama, who succeeded to be a thangka painter. Ole Nydahl invited her two or three times. And one time, in 1993 Bruni and I were painting a big wall-painting, the wheel of interdependent links, in Denmark and Ole was there and invited Bruni again. But she did not like to go to Russia for teaching, and then I said I could go. Ole was glad. He organized it. And the first year they sponsored the whole course, so the group did not have to pay, but the German Kagyu group did it. Gabi was responsible, she organized everything. |

| Question: Did Gabi find the participants of the retreat? |

| Answer: Yes, she found sponsors and organized the whole course. Don't forget that Ole's Russian students did again and again ask for someone teaching on thangka-painting. And it was the first time. And it was funny here, because at that time I moved from one house to other house. It was in the beginning of February, and in March we were in Denmark, and Ole agreed that I would come. And then I was just at home, and the telephone was just attached to new connection, it was seven o'clock in the morning. And there was a ring, and they asked me: Marianne, could you come to Russia? I went for the first time in my life to Russia. And I was gone; I think it was June, or July. And also that year my mother was ill and died. Yeah, every year I came, except two years: my husband became very ill in 2002 and asked me not to go, and the year after his death I also did not go. So since 1993 I came and this is my 14th time. |

| Question: What development has happened within these 14 years, what has changed in Russia, in students? |

|

Answer: The first students I still have: they are

Tanya, Misha, Natasha Machs. I still meet them, and they have contact with

me. I saw in the beginning that the financial situation was very poor. I

remember that during some years people could hardly pay for the course. And

I remember — especially Ukraine, don't remember the name of the place — Phowa was there. Ole had just been there, and they organized my course

immediately after the Phowa. I saw that there was a very bad financial

situation. And they have even hidden some students, so that no one knew that

there were some extra students, and they took the food extra so that to take

to them, and they shared the bed, and so on, that kind of situation. The

official office did not know that there were some extra people. Of course,

the organizer of the course knew. But those who gave the building, the food,

and so on, they did not know. And especially Ukraine, it was so poor. I

remember that it rained heavily, and it rained down the staircase, like a

waterfall.

Also Vika from Saint-Petersburg was there. I have been to many places: several times to Ukraine, I have been in Kalmykia, between the Caspian and the Black Sea, in Buryatia, Saint-Petersburg three or four times, Moscow I think now eight times, at the Ladoga-lake, in the North-West close to the Finnish border. And we lived in the place of the woman, she was connected with the Hermitage, she was a photographer, who photographed for the catalogues and so on, for the Hermitage. And it was the first time Larisa translated for me. |

| Question: And it is interesting, did such material problems, limitations affect somehow the works, the style? |

|

Answer: Let me say, that Russian people are very

devoted. Very active, they want very much to learn, and put much effort.

Most of the time most of them were working until two or three in the night.

They could not be stopped, so they continued and continued. Sometimes I came

in the morning, and some of them were sleeping over their work! I had never

met such enthusiasm. I don't know till when they work here, I have not seen,

not so long, not very late, I think? (Till one — two...) Aha? I didn't know.

And I also remember that in the beginning I had to buy some materials like

brushes and paints (Windsor and Newton) in Holland — the students ordered

for them and I brought them with me. And now everything is available. Is it

so? Can you buy every colour?

(Zalina and Alla: There is nothing here! We were lucky when we painted Dorje Chang, we managed to buy the colours we have never seen in our life. That's how the blessing works! And now, ther is nothing there again! But we think the situation will change. We remember how we were looking for glue all over country, and now it is available everywhere. Misha and Tanya told us that they were looking for some paints in garbage, since there was lack of paints). And now I think all Russia is comparable with this special region of Moscow, and even to Holland, to the West. Of course, I lived in many-many different houses, but I think the last years I lived in more luxurious houses; at first I experienced very small apartments with very small space. In the beginning I was amazed, how many people could fit into a small kitchen two by two, let me say. And also I noticed the sense of solidarity, though the level of life was so low, that people who could not pay for anything were sustained by others who also did not have so much money, they paid for those, so that they could learn. And what I also liked was the contact ability: people touch each other; it is not done in our country, almost not. I remember the banya, where people washed each other — hair, and so on. It was astonishing! I did not get used to it at all! |

| Question: And such a question: which qualities are developed by thanka painting? |

|

Answer: Because you have to use the Six Paramitas, it

has a big impact on your life! It takes you a lot of time, you need long

time for sky, and sometimes you are fourteen days only on one sky. So you

give your free time, and also you need patience — a lot of patience. You

need enthusiasm; you have to stay on, to continue the process. And you need

to put effort in it, because it is not always easy. I remember the

situation, when I had to finish a big thanka, it was so hot in my studio,

sweat covered all my body, and I had to put something beneath my hands so

that I would not lose sweat on the painting. And there was really effort I

put in it. And then, you need concentration, of course, lot of

concentration. You have to find pictures, you have to look in books, be

attentive. You have to invent many things. Wisdom is expressed in such a

way. So I'm shaped by that, I'm shaped by those paramitas. And, besides, of

course, my spiritual practice. I got for painting different initiations,

e.g. one needs to have highest Annutara-yoga-tantra initiation when you have

to paint a deity in that category. It all has to go in combination.

I remember, my teacher Gelek Rinpoche asked me for a big thangka, I remember I was sitting in America in his house, together with him, and no one else was in the house. I asked him: what could I paint next? Do you have an idea, because I did not know. He said: "Oh, you paint a field of merit". I said: "You don't mean the big one with all the figures on it!" He said: "Oh yes, I mean it". So, sometimes he was in Holland, and I asked him, could you please pass by and look if I'm doing well. He was there. I remember that there were people from everywhere: from Taiwan, Malaysia, Germany, Holland etc., about ten people were in my studio looking on the thangka, and he was sitting there and he was explaining. It was very nice. He visited my house, and they all looked at my thangka with all those people around. Sometimes I asked him to come, and he said: no, I don't come, I don't come. But I put some pressure on it. I said: "I need some support". "You have support all the time", he said. And when I was painting, a Tibetan person was standing behind me. A woman saw me in a vision, a clairvoyant. Clairvoyant means such a person who sees more than normally is seen. It is clear view. It is more a spiritual experience, when you see extraordinary things. There are some people who have a gift to see more than normal people. A special woman saw at a certain moment in a dream that I was painting a big painting, and that behind me a Tibetan person, so he was guiding me, a man was observing my thanka painting. She saw that. Behind me there was a master, a man was guiding me in the backside. That lady was a friend of a friend of mine. She told her: do you have a friend who is making a big painting? And then my friend said: yes, I know someone. And she said: a Tibetan is behind her to guide her. So, sometimes things happen. |

| Question: Was it when you painted the Refuge Tree? |

| Answer: Yes. And also the Tibetan master was in my house, and he had a look at the painting from behind. |

| Question: How long did it take you? |

| Answer: That thangka took me three years. I consider that period as a kind of three-year-retreat. |

| Question: And how long does it usually take you to paint a thangka? |

| Answer: It depends, of course, on how big it is, normally it takes six weeks. And ...) I paint six hours a day, five days in a week. So, thirty hours a week. I think one thanka will be six times thirty hours… About hundred eighty hours. And when it is bigger, I need, of course, more time. |

| Question: What is now main occupation for you — painting or teaching? |

|

Answer: Both supply each other. So, I like to teach,

and that will be possible till I'm very old. But whether I will be able to

be a thangka-painter for more then several years again — that is a big question. May be, hands will be trembling, or eyes will be bad. Until now it goes well. |

| Question: Do you mainly paint by order or for yourself, for your friends? |

| Answer: Mainly I am asked to paint a certain thangka; but now, with these financial bad times, I also experience the recession. When I have no request then I paint something that I liked to paint already earlier. In that way I painted e.g. the Kalachakra and a Vajra Yogini in her light-palace. And I have recently painted Machig Labdron, which I also wanted to paint for a long time. It is for the Chod practice. |

| Question: And such a question: this is the first time that the retreat on thanka painting is held here, in the retreat center near Kaluga. How do you like the place, which is called "Buddha's Place of Enlightenment"? |

| Answer: Now I like it very much. I even prefer it to Kunsangar, the first time I liked it very much. But last year there was a big group of 200 dancers, and there was so much noise. But here I like the nature very much, the landscape. I have never seen such a lot of flowers. So beautiful colours. And all these hills. And I think it will be a very nice center. I heard that a big temple will be built here. And of course, you see only beginning here, but you see how many people are here, especially at the weekends, how crowded the bathroom is, and shower, you hear the water all the time. I am sure there will be big differences in some years. |

| Question: Which qualities should a thangka painter possess? |

|

Answer: He must be devoted, have Guru devotion,

because without it nothing is possible. He must be humble, not having that

much ego. Certain ego is necessary, let us say, it is not ego, but it is

more feeling kind of self-estimation, that you are able to do it. And as a

teacher one has to be convincing, you have to study yourself, you must know

what you tell, to be able to give people knowledge, to give new things.

Money should not be the main reason to paint. It is nice when you earn some

money with it, but when you feel that there is someone who needs a thanka,

and there is not so much money, you just give it or they pay a little money.

And also one should be loving, because if there is no love and estimation

for someone, than you judge on good or bad work. You know, that even a

drawing or painting is not that good, you see that someone put effort in it;

so you must have love and compassion. And you should diminish your needs

because of others also, because it is really sometimes tiring — to teach day

after day, after day. And there is not so much time for yourself, to do

other things.

There was a time when Gega Lama was giving teachings on what is the function, the duty of a teacher towards his students. And he explained at least two hours. The main thing he said, that teacher, when he is still alive, he is and stays the main for his/her students. When a student will be able to teach the teacher will say: you can start with easy things and I will tell you when you can overtake my duty. So with that in mind I was always a little bit… I felt bad about it, I never asked his permission, although I was asked by my teacher my teacher Kyabje Gelek to come to America already four times. So I was asked by my own teacher but I never asked Gega lama so I wanted his permission to teach myself. And I remember that a friend of mine, she went to Katmandu and she asked me should she take something for Gega Lama; so I had some presents for him, I wrote a letter, I let it to translate in Tibetan, and she took it with her, and she took also a bunch of papers — translation of some chapters of his book, Gega's book. In Russian — I still have those chapters at home. So she took it also with her; in that letter I asked Gega Lama: do you think, can I teach, because I do already and I feel bad about it, that kind of thing. And my friend-made took some pictures which showed that Gega lama was reading my letter, and it was seen he was already very ill, and he would not live very long after it. Then, after some weeks, after two weeks I got a letter, he sent it from Katmandu, and he said: if you are asked for one person even, then you have to go. That is how I asked his permission. By him I got a teacher's name that is painter's name. Tashi Palmo, the one who has an abundance of capacities. It is very beautiful. And than after two or three weeks, I think, he died. I was just in time. I would have had a very bad feeling if I would not have asked in time. But he was so careful, he also was talking with so much love about his own teacher. And he showed also how important it is — the lineage, and how precious it is, to have a lineage. A woman from Holland, she went regularly to Gega's studio, and there should have been eight or ten people working every day. Lakshmi was her name. She was very young, she was eighteen, she had very long hair. She wanted to be a thanka painter, and she went to Katmandu and stayed there for half a year. All men, the male painters were making jokes on her, pulling her on her hair, because she was the only woman there. Then she met Gega's son Tharphen, and he at that time did not want to be a thanka painter at all, he wanted to go to America and earn quick money. And because Lakshmi he became a thanka painter. And they are living in Holland, they married, they have two boys. I met him on the 3rd of July in Amsterdam. They had there an exhibition. He is a very sweet man. He is e very kind and gentle man with many capacities, maybe he is around the thirties. So, because of a Dutch woman he came to Holland and became a thanka painter. He teaches now in Belgium, in the same place where I got teachings from his father, Gega Lama. |

| Question: How old is he? |

| Answer: He is a young man, I think, not yet thirty, 27-28. |

| Question: May be your children or grandchildren will take over you? |

| Answer: Oh no, for sure not. My daughter is not interested at all; my two sons are also not. Though everyone has a Buddha-statue and a thangka in the house, but no one will take my stick. And I suppose no one in Holland. I have no idea about it. I try; I do my best to find someone. I had a very good student, but she died of cancer some years ago. And there was also another woman, who was very much interested in thanka painting, but she also died of cancer. So I think that son of Gega Lama… At least the lineage will continue. |

| Question: We hope that it will never be broken. Thank you very much that you come here to us year after year. May be you want to make some wish or to give a piece of advice to your Russian students? |

| Answer: Continue the way you do, I would say. |

|

|

|

15.09.2019 |